Ceres: Dwarf planet is pocked with craters, NASA’s Dawn spacecraft shows

NASA’s Dawn spacecraft has snapped the best images to date of the dwarf planet Ceres, bringing mysterious fuzzy features spotted on the icy little world’s surface into sharper focus.

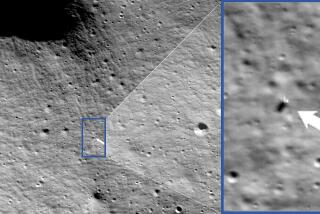

The latest images were snapped on Feb. 12, when Dawn was 52,000 miles away from Ceres and closing in fast -- it’s scheduled to enter orbit on March 6. The new images have a resolution of 4.9 miles per pixel, and these unprecedented views are revealing a surprisingly cratered surface.

Ceres is the largest member of the asteroid belt, the ring of rocky debris between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Asteroids are the leftover building blocks of the planets -- floating fossils that could teach scientists much about the young solar system.

Among these space rocks, Ceres possesses a special combination of traits that make it ideal for study, said Carol Raymond, Dawn’s deputy principal investigator and a geophysicist at Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“The really neat thing about Ceres is that it’s kind of straddling a lot of boundaries between ... the rockier asteroids in the inner part of the asteroid belt, and the wetter asteroids in the outer part of the belt,” Raymond said.

That’s because the rockier asteroids are closer to the sun and have lost the water they once had, while the more distant asteroids are beyond the solar system’s “snow line,” and cold enough to hang on to their frozen water.

In its key position, this dwarf planet has extremely cold spots and not-so-cold areas. Beneath the thin surface layer that varies with the day-night cycle, Ceres is roughly minus-100 degrees Fahrenheit around the equator and minus-225 degrees Fahrenheit around the poles. So at the chilly poles, Ceres may have some features similar to outer-belt asteroids; and its slightly-warmer equator might showcase features that look more like those of inner-belt objects.

“I really think we’re going to learn a tremendous amount,” Raymond said. “Ceres is just such a unique object that by studying it, there will be implications for many other types of bodies.”

Many expected that Ceres, thought to be full of water, would have a smooth, icy surface (particularly around the midriff). That’s because ice on a roughed-up surface tends to relax over time. But these new images contradict that theory.

“The whole surface appears to be cratered. It doesn’t appear to have a very smooth surface like might have been expected,” Raymond said. “All in all, it’s just looking really interesting.”

This could mean that there’s a lot more rock mixed in, keeping the surface from smoothing out over time -- though it’s unclear how the rock might have gotten there. It could have been brought by debris smashing into Ceres, or by convection as ice moving through its layers pushed rock upward.

Ceres is one of a few “water worlds” in our own solar system, such as Europa and Enceladus, that may have held a subsurface ocean in the past (and in some cases, may still be hiding one beneath an icy shell). Such worlds have the potential to be habitable for microbial life.

The dwarf planet is actually Dawn’s second target; the first was Vesta, the second-most-massive asteroid in the belt and another giant building block from the solar system’s early history. These two bodies have ended up looking very different: Vesta is lumpy and dry, while Ceres is spherical and wet. Their divergent life histories could shed light on the solar system’s evolution.

Follow @aminawrite for more science news that’s out of this world.