Juan Antonio Samaranch dies at 89; longtime Olympics chief

Juan Antonio Samaranch, former president of the International Olympic Committee who took the organization from financial instability and turmoil and steered it to global influence and prosperity, only to see his legacy tarnished by the specter of doping in sports and a corruption scandal, has died. He was 89.

A Spaniard who served as IOC president from 1980 to 2001, Samaranch died Wednesday at a Barcelona hospital after experiencing heart trouble. He had been in failing health since he collapsed one day after the last of his four terms ended, in July 2001.

Samaranch, who was both politician and diplomat, honed his skills over two decades as a government official under Spain’s fascist dictator, Francisco Franco. During Samaranch’s tenure, the Games became a global television event, one funded primarily by corporate endorsements.

For all his successes — achieved with what was often perceived as an authoritative grip — Samaranch was never able to control the use of performance-enhancing substances by Olympic athletes. Critics said he had no desire to wade into the controversy.

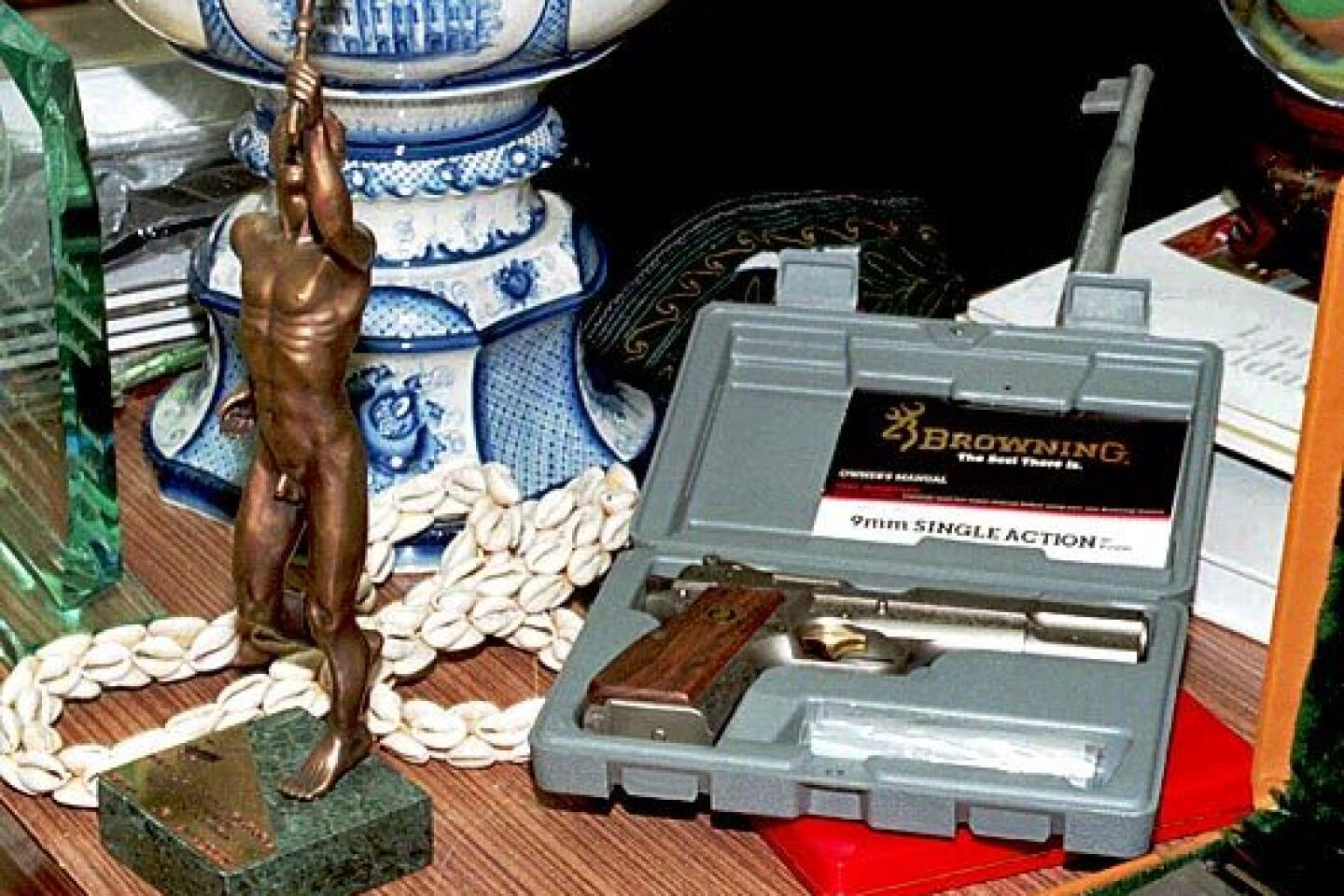

Late in his presidency, a corruption scandal erupted amid revelations that bidders in Salt Lake City had showered IOC members with more than $1 million in cash and gifts in a winning campaign to land the 2002 Winter Games.

Of the IOC’s first seven presidents, Samaranch was the most important in 105 years, said John Lucas, a Penn State University professor emeritus and an Olympics historian.

“This does not mean he was a man without flaws or one who did not make serious errors,” Lucas said.

Current IOC President Jacques Rogge compared Samaranch with Pierre de Coubertin, IOC president in the late 19th century.

“De Coubertin created the modern Olympic Games,” Rogge said. And in the late 20th century, “Samaranch created the modern Olympic movement. He had a clear vision of what was needed. And he had the time to do it.”

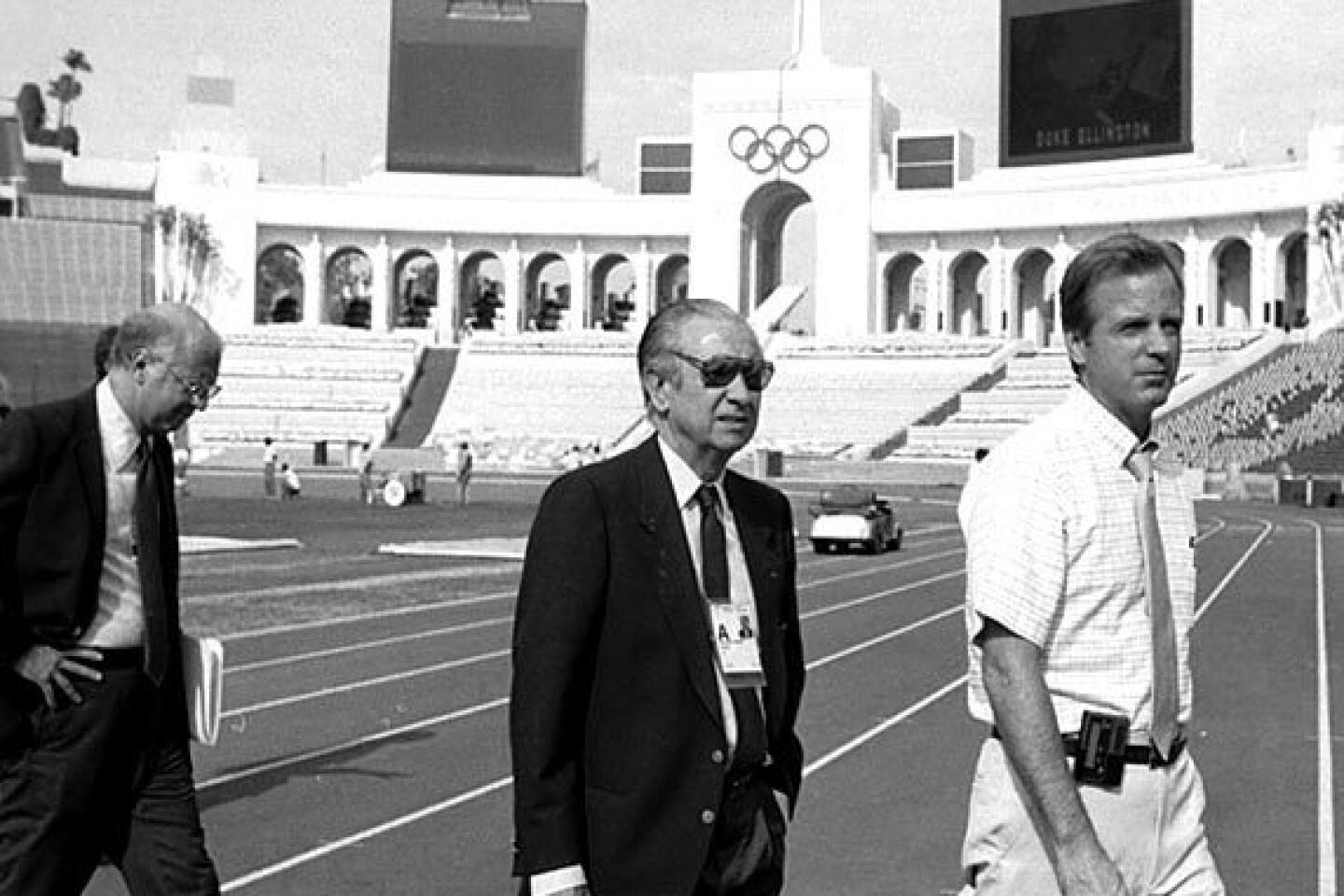

Peter Ueberroth, chairman of the U.S. Olympic Committee from 2004 to 2008 and chief of the 1984 Los Angeles Summer Olympics — the Games that launched the economic transformation of the movement —observed: “He really did an incredible job of taking an institution that had very little net worth and very little direction and making it arguably one of the two or three most powerful [non-governmental] organizations in the world.”

The IOC that Samaranch took over in 1980 was a club made up mostly of white men from Europe. It faced severe financial pressures.

Now the IOC is a billion-dollar enterprise supported by many of the world’s leading multinational corporations. Thanks to his efforts, the boycotts are over. There are more member countries in the IOC than in the United Nations.

The IOC includes a significant number of delegates from the Third World and some women. Female athletes have taken part in increasingly large numbers at the Games. Professional athletes, the best from each nation in each sport, now take part in the Games.

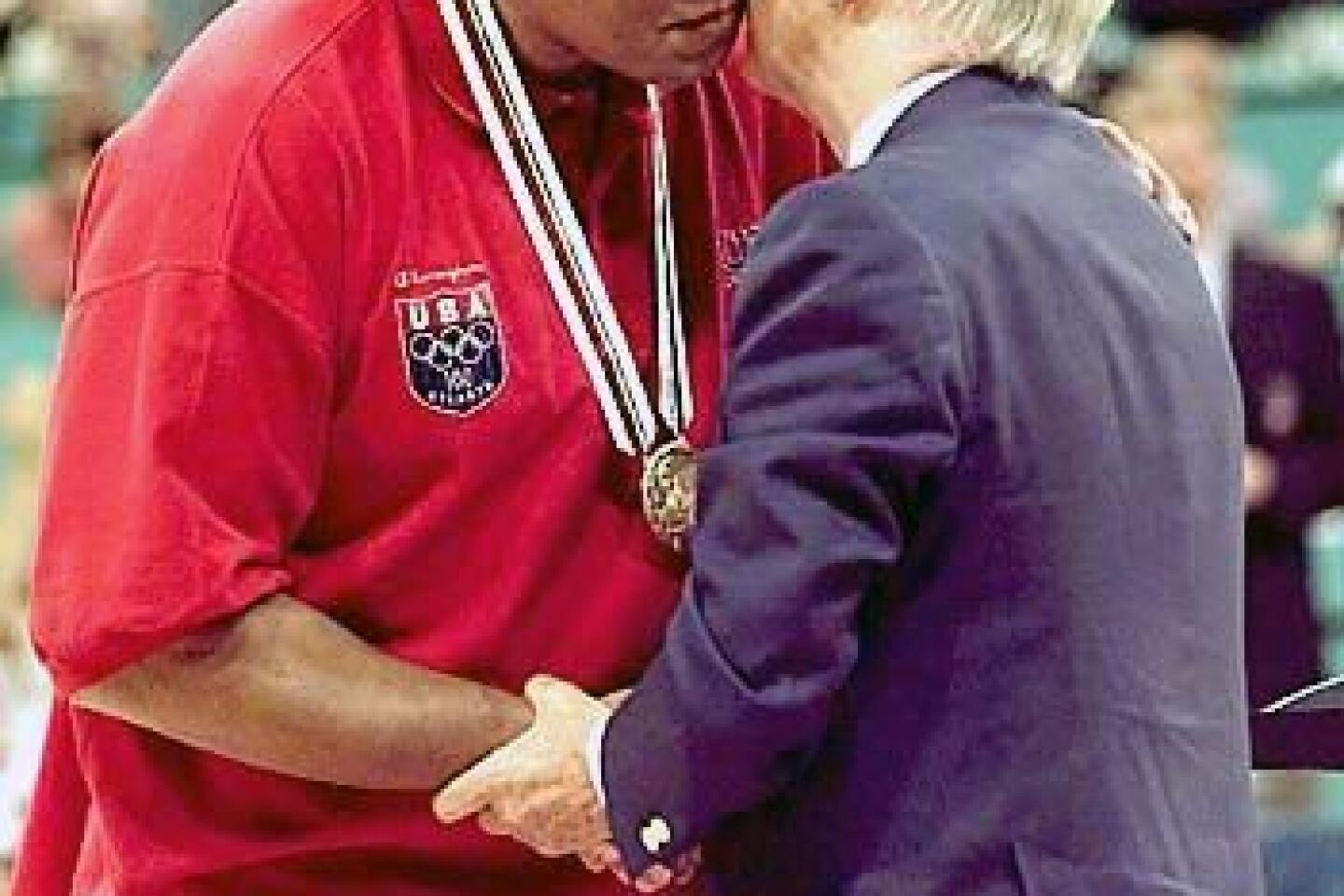

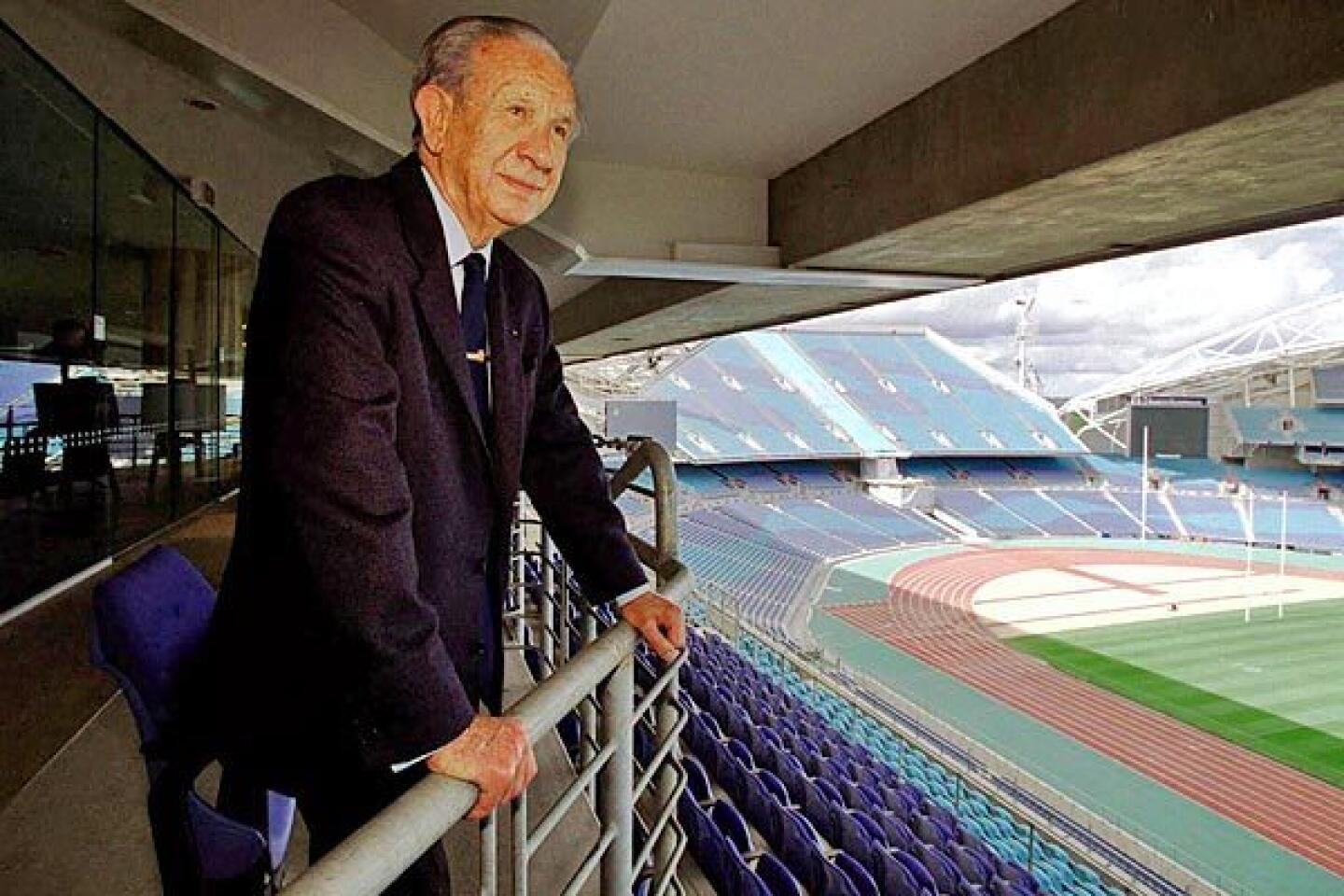

He was fanatically devoted to the possibilities of the Olympic movement, arguing that the power of sport could advance the cause of world peace. At his last Summer Games, in Sydney in 2000, Samaranch engineered the joint procession of athletes from North and South Korea — two nations still at war — in the opening ceremony.

Throughout his presidency and beyond, Samaranch remained a source of controversy.

He either did not know — or did not want to know — the scope and nature of institutionalized doping that came to plague the Olympic movement, and in particular the wide use of anabolic steroids that characterized the Olympic sport system in the former East Germany.

In 1998 the Salt Lake corruption scandal erupted on Samaranch’s watch. It led to the resignations or expulsions of 10 IOC members and to the enactment in 1999 of a reform plan that included a ban on visits by IOC members to cities bidding for the Games.

The Salt Lake City scandal sparked savage criticism worldwide of Samaranch, and many calls for him to resign, which he resisted. He was typically described as aristocratic, aloof and out of touch; reference was often made to his suite at the Palace hotel near IOC headquarters in Lausanne, Switzerland, his base for many of his years as president.

The fifth-floor suite actually consisted of two rooms — a bedroom with a ratty blue blanket from the Lake Placid Winter Games of 1980 that Samaranch draped over his bed and a living room where he frequently worked into the night.

Samaranch’s life was full of such contradictions.

He worked for 21 years as IOC president without being paid a salary. His expenses were reimbursed, including about $200,000 annually for the Palace suite. Experts in executive compensation said he was a bargain.

Much of the world saw him as imperious or autocratic. Family and close colleagues said he was shy but generous, patient, sometimes even impishly funny.

The son of a textile manufacturer, Samaranch was born July 17, 1920, and studied business in school and boxing in the gyms of his native Barcelona. In his 20s, he played roller hockey and dabbled in sportswriting. He was known as a ladies’ man.

At 35, in a union that cemented his station in Barcelona society, Samaranch married Maria Teresa Salisachs-Rowe. Salvador Dali designed their wedding menu card.

As a deputy sports minister in the Franco government, Samaranch was inducted into the IOC in 1966. In 1973, he was named president of Catalonia’s provincial government.

In 1977, two years after Franco’s death, Samaranch became ambassador to the Soviet Union.

His relations with the Soviet bloc helped propel him to the IOC presidency, but he was dogged by his association with the Franco regime.

Andrew Jennings, a British author of books sharply critical of the IOC and Samaranch, said, “What the Olympic movement didn’t want to take aboard was that this man was a fascist by choice. This was not an accident. The fascist attitudes he brought together in his 20s, 30s, 40s lasted all the way through his life and did incalculable damage to the Olympics because he believed through that credo in trickle-down power. He thought democracy was foolish.”

Samaranch “made corruption a formal part of his policy. This was something he learned from the Franco regime: You gave your lieutenants the opportunities for corruption; it bound them more loyally to you,” Jennings said. Many “of the members he selected during his tenure were people he knew would seize these corrupt opportunities in their many forms.”

Samaranch insisted that his time in Spain could be judged only by Spaniards.

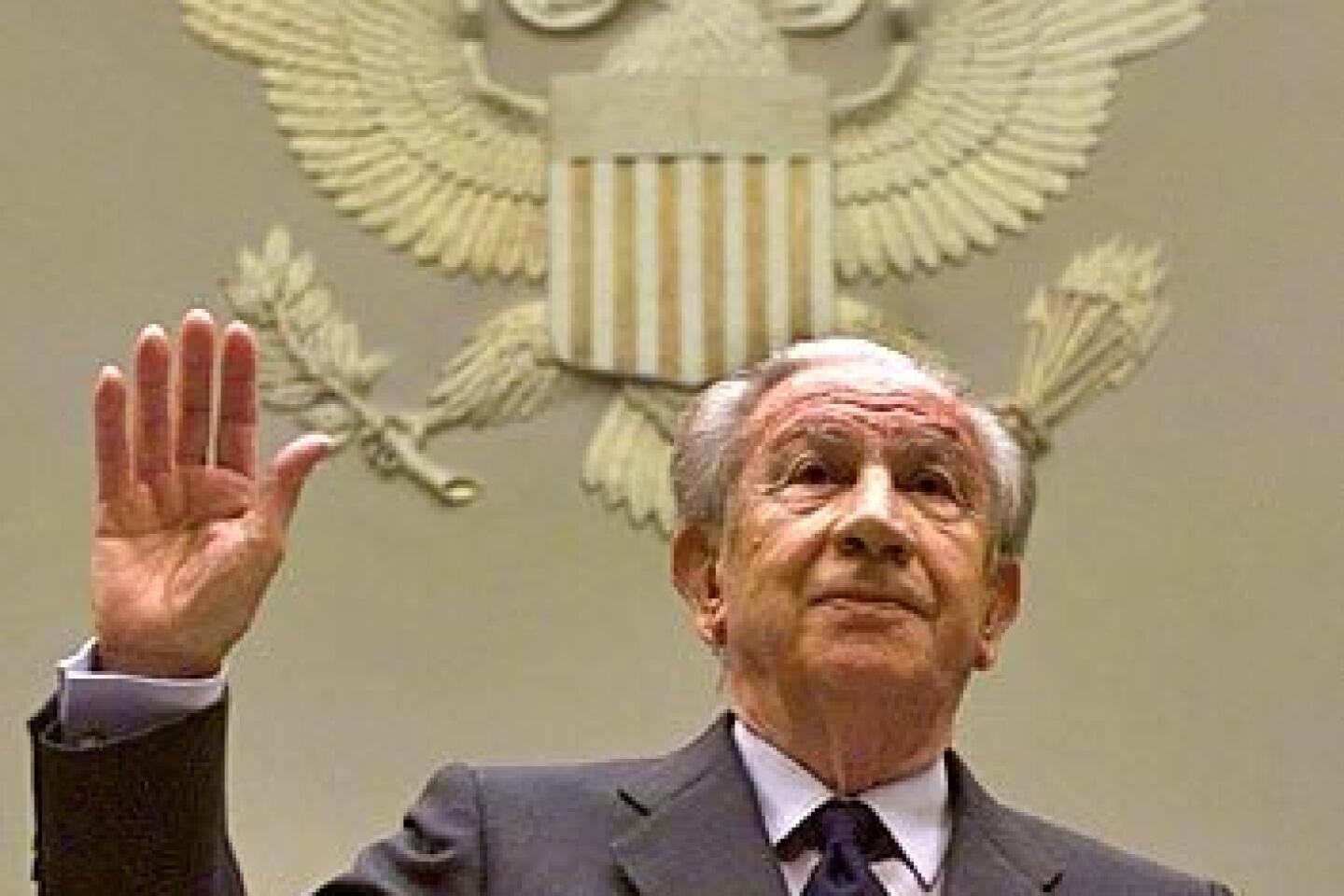

Before he testified in 1999 in front of the U.S. Congress about the Salt Lake scandal, Samaranch anticipated that he might be asked whether he was fascist.

“It is not true,” he told NBC executive Dick Ebersol, who recalled that Samaranch went on to say, “All of us who have lived under conditions like that have at some point or another been a part of things because we wanted to be involved in the life of our country — and for me, it was sport.”

Elected IOC president in July 1980 in Moscow, Samaranch inherited an organization beset by problems.

The Summer Games in 1972, 1976 (Montreal) and 1980 (Moscow) were hit by boycotts and, after Samaranch took over, the Soviets retaliated by skipping the 1984 Los Angeles Games. The Montreal Games ended up with a $1-billion cost overrun. And in 1980 the IOC itself had little in its bank accounts.

Samaranch had long seen, however, that the IOC’s financial future lay in the sale of television rights and in marketing the five interlocking Olympic rings to major corporations.

Ueberroth provided the working model: The 1984 L.A. Games turned a $232-million profit.

In the mid-1980s, the IOC began a concerted marketing program; today the Olympic movement’s revenues top more than $1 billion annually.

TV emerged as — and remains — the IOC’s most important source of revenue. NBC, the IOC’s single-largest financial underwriter, agreed in 2003 to pay slightly more than $2 billion to televise the 2010 Winter Games and the 2012 Summer Games.

John MacAloon, a University of Chicago professor and expert on the IOC, maintains that the financial growth of the IOC is secondary to Samaranch’s larger accomplishment, a political transformation.

Samaranch’s political savvy brought the IOC influence within the United Nations and non-governmental organizations and the complex circle of key Olympic players — primarily the international sports federations and national Olympic committees.

“An astonishing transformation,” MacAloon said, adding, “That to me was his real genius.”

Samaranch also set out to broaden the sweep of the Olympic movement.

He actively recruited IOC members from developing nations and increased funding for their activities. He opened IOC membership to women. And he sharply expanded the number of women’s sports at the Games. “I call him the president of inclusion,” said Anita DeFrantz, the senior U.S. IOC member.

Professionals were allowed in — such as Michael Jordan and the U.S. basketball “Dream Team” that dominated the Barcelona Games in 1992. But the appearance of such stars sparked concerns that the Games have become too commercialized.

A business approach to the Olympics was nothing new, though. Insiders had been aware of extravagances that came to be associated with the process by which cities bid for the Games as far back as 1985 — the year after the L.A. Games proved there could be big money in landing the rings.

Why Samaranch never launched an investigation of the questionable practices is an enduring mystery.

The answer may lie in Samaranch’s management skills and personality traits. His strategy was to identify those who opposed him on a particular issue and, over time, bring them into the so-called “Olympic Family” with the hope of moderating that opposition.

Jean-Claude Ganga of the Republic of Congo, for instance, was a leader of the 1976 African boycott of the Montreal Games. He was selected by Samaranch to join the IOC in 1986. Later, he was revealed to have been the chief abuser of the Salt Lake largesse. According to court papers filed in Salt Lake, Ganga received $320,000 in cash and gratuities.

“It was much better to have him inside than outside,” Samaranch, speaking of Ganga, once told The Times.

But he also said in a later Times interview, “I regret, I really regret, what happened in Salt Lake.”

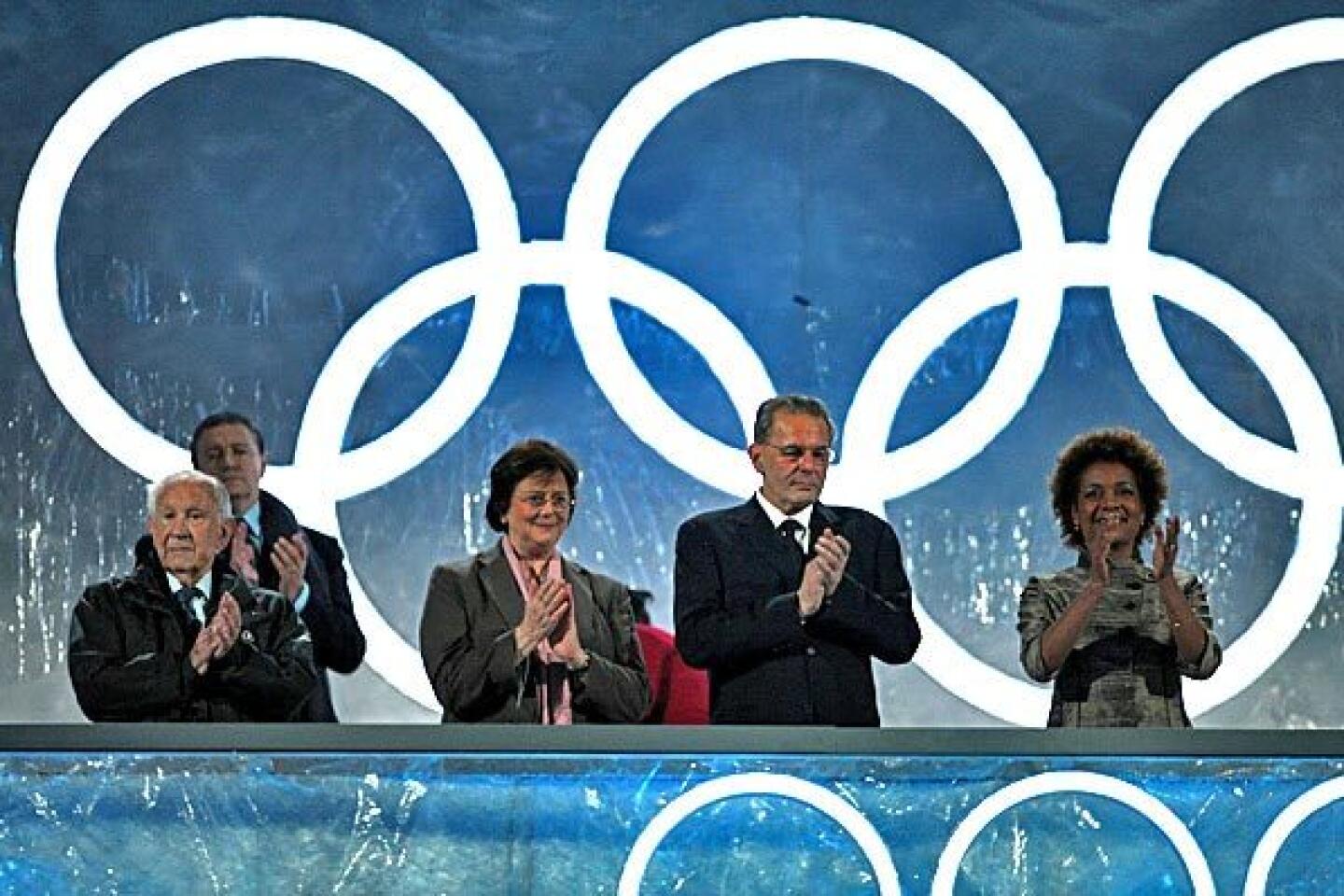

After his presidency ended, Samaranch was named IOC honorary president for life.

His style prevailed until the end, and his influence never waned because 70 of the current 114 members were nominated or elected during his reign.

In his final days as president, he assured the election of his son, Juan Antonio Jr., to the IOC. In July 2007, he called in old chits to help Sochi, Russia, get the votes to become host of the 2014 Winter Olympics.

He also made what amounted to a deathbed plea on behalf of Madrid during the Spanish capital’s presentation before the October 2009 vote for the 2016 Summer Games.

The members’ regard for Samaranch was enough to allow Madrid a respectable defeat against Rio De Janeiro in the final round.

Samaranch’s wife of 45 years, Maria Teresa, died in 2000 in Barcelona as her husband was presiding over his last Olympic opening ceremony in Sydney. Besides his son, he is survived by his daughter, Maria Teresa, and seven grandchildren.

A funeral is planned for Thursday in Barcelona.

Abrahamson is a former Times staff writer.

Tribune Olympic writer Phil Hersh contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.