In India, agriculture’s Green Revolution dries up

India’s Punjab is running out of water. High-intensity agriculture has also exhausted or contaminated soils, depleted streams and aquifers, and led to resistant pests.

Surjit Singh, a farmer in India's Punjab state, fell into debt as he spent more to drill deeper for water in ever shorter supply. ( Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times )

July 22, 2012

LUDHIANA, India — Propping a bare foot on a circle of bricks, Surjit Singh stroked his white beard and recalled how water once flowed from his well.

It was decades ago, when hybrid wheat seeds arrived from Mexico, each supposedly capable of producing a sturdy plant with fat heads of grain.

Young and ambitious, Singh signed on to a new way of farming, spreading fertilizer and pesticides generously along with the new seeds. The Indian government guaranteed a minimum price for his grain and provided free electricity to pump as much groundwater as he wanted.

The results seemed nothing short of a miracle. Before, Singh had been able to coax a single crop from his 2½-acre field. Now he could plant wheat in summer and rice in winter, and harvest two or three times as much of each. Punjab state became India's breadbasket and turned a starving nation into a food exporter.

After a few years, though, the gush of water from Singh's well slowed to a trickle. He had to sink a deeper well and buy a bigger pump. The cycle continued until he was forced to abandon the well and bore a much deeper one on the other side of his property.

Today, the Punjab, whose name means "land of five rivers," is running out of water.

The thump of well-boring rigs echoes across the plain. Farmers try to drive wells deeper than their neighbors'. The water table is dropping at a rate of about 3 feet a year.

High-intensity agriculture has exacted other costs: Exhausted or salt-contaminated soil, resistant pests and plumes of fertilizer and pesticides in streams and aquifers.

Similar problems have arisen around the world. Agriculture accounts for more than 90% of all the fresh water used by humans. Demand is so great that many of the world's mightiest rivers no longer reach the sea year-round. Grain farmers in the top three cereal-producing countries — China, India and the United States — are pumping water from aquifers faster than rainfall can replace it.

Punjabi farmers produce more than half the grain sold commercially in India. But production is not keeping pace with demand from a growing population. Shorter, more sporadic monsoon rains associated with a changing climate have made matters worse.

"Punjab, the most stunning example of the Green Revolution in India … has become unsustainable and non-profitable," the Punjab State Council for Science and Technology said in a 2007 report.

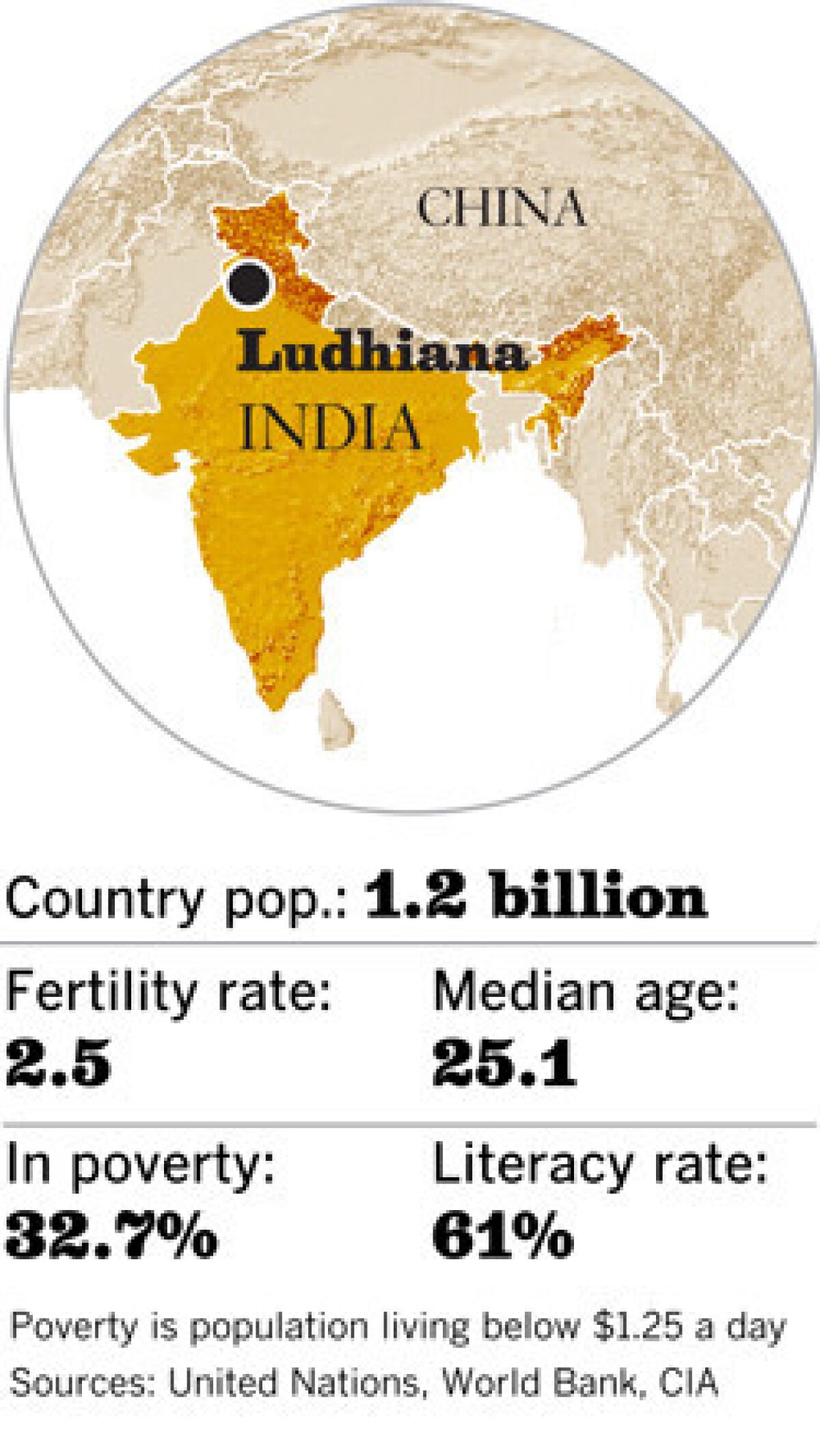

Punjab Agricultural University, dedicated to "ensuring food security to the nation," has a population clock on its website, reminding students and researchers of the challenge ahead: India's population of 1.2 billion is on course to reach 1.4 billion by 2021, exceeding China's.

"If these grains were not available from Punjab, this country would starve," said S.S. Johl, an emeritus professor of economics who has spent 60 years helping to bring modern agriculture to Punjab.

"We need to put more emphasis on family planning and controlling the population," he said. "If this race keeps up, the day is not very far when the population will overtake production."

Singh looks back at his decades of modern farming with regret. As his expenses mount, banks and agriculture cooperatives will no longer give him loans, forcing him to turn to hard-nosed money lenders who charge 24% interest.

Now in his 60s, with bowed legs, Singh cannot think about retiring. "Day by day, the debt level is increasing and the confidence level starts coming down," he said.

He grew quiet, wiped one eye with a calloused finger and straightened his turban. He said he understood why thousands of Indian farmers have committed suicide in the last few years, hanging themselves, drinking pesticide or jumping into dry wells.

"When they see they cannot repay the amount and their income is very meager, then this is the only step left."

About the series

Los Angeles Times staff writer Kenneth R. Weiss and staff photographer Rick Loomis traveled across Africa and Asia to document the causes and consequences of rapid population growth. They visited Kenya, Uganda, China, the Philippines, India, Afghanistan and other countries.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.