L.A. Unified alerted to possible sexual misconduct by Berndt in 1983

In 1983, a South Los Angeles elementary school principal received a call about one of his teachers, a 32-year-old just a few years on the job. On a student field trip to a museum, Mark Berndt had dropped his pants, a parent complained.

The principal called the parent back and jotted notes about the incident in a memo. Berndt remained at the school.

“Thanks again for the support you gave me,” Berndt said in a handwritten note to the principal shortly after the complaint. “I did learn at least one thing for sure! Not to take students to the museum while wearing baggy shorts!”

Three decades later, Berndt would become the focus of one of the largest sexual misconduct scandals in the history of the Los Angeles Unified School District. Documents recently made public in civil lawsuits brought by students and their parents show the district had multiple prior complaints about Berndt over his 32-year career at Miramonte Elementary School.

The May 1983 memo by the principal and Berndt’s response show that a supervisor was alerted to possible sexual misconduct by Berndt a decade earlier than the previously disclosed allegations. Other newly released documents show that students, parents and other teachers were alarmed by Berndt’s conduct over the decades he spent working at Miramonte.

His frequent hugging of students and penchant for shorts — some tight and revealing, others overly baggy — was well-known at the school, several witnesses said.

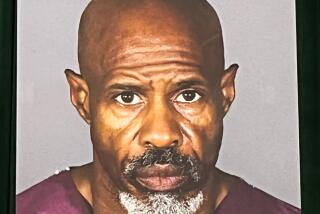

Berndt taught at Miramonte from 1979 to 2011, when investigators began to look into his conduct based on photos turned in to police. He was later accused of spoon-feeding his semen to blindfolded students as part of what he called a “tasting game.” Now 63, he pleaded no contest last year to 23 counts of lewd conduct and was sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Sworn testimony from students in the new documents details the harm left in his wake. One seventh-grader testified earlier this year that she is now wary of her teachers, has trouble trusting others and no longer goes anywhere near the boys in her school.

“Has it made you feel safer knowing that ... he’s in prison?”

“No,” she replied. “Anybody else could do it.”

The documents were filed by attorneys and their families trying to prove that the district should be held liable because its employees should have known about Berndt’s behavior long before his suspension in 2011. The district has filed papers asking for some of the claims to be thrown out, arguing, for example, that there is no proof that the parents were harmed as a result of Berndt’s actions.

District spokesman Sean Rossall declined to discuss the complaints against Berndt “out of respect for the students and families involved.”

“One thing is clear, Mr. Berndt went to incredible lengths to conceal his misdeeds,” Rossall said.

The new release of documents comes after a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge overseeing the case ruled that much of the evidence in the civil trial can be publicly disclosed, except for names and identifying information of victims and their parents, police investigative reports and Berndt’s personal information such as his Social Security number.

“The parties cannot shield information from disclosure merely because it is damaging or of an upsetting nature,” Judge John Shepard Wiley Jr. wrote.

The district last year agreed to pay $30 million to settle 58 claims brought by those victimized by Berndt, about half of the students who have filed claims. The judge is scheduled to hear the district’s motions on the remaining cases Oct. 7.

It’s not clear from the 1983 memo what action, if any, the school took against Berndt over the parent’s complaint. The school’s principal at the time has since died, the district says.

In the early 1990s, his successor received complaints about the teacher when several fourth-grade girls went to the principal alleging that Berndt was regularly masturbating in class, the former students recalled in testimony. The principal dismissed the claims and accused them of lying, the former students recounted.

“I don’t think they took us seriously,” one said.

About the same time, a young teacher was observing the class when Berndt, clad in loose-fitting shorts, sat in a way that exposed his genitals, the teacher later recalled in a deposition. She said the students turned back at her and met her eye, as if to make sure she knew of their discomfort.

She marched into the office of yet another principal to complain, the teacher recalled. But the principal wasn’t surprised.

“I know, baby. I’ve had several complaints from parents, too, but there’s nothing we can do about it,” the teacher recalled the principal saying.

That principal denied ever receiving such a report, calling the teacher a liar. She also denied knowing about any past complaints about Berndt’s behavior, saying that she had never seen the 1983 memo.

In 1994, a student reported that Berndt, while grabbing some papers, reached past her desk and touched her inappropriately. That incident was reported to the police but dropped after investigators concluded there was insufficient evidence.

Former senior district administrator George McKenna, who was elected last month to the Board of Education, suggested in testimony that inconsistent record-keeping may have led the school’s principals to treat complaints as isolated incidents.

Asked about the 1983 memo, McKenna said it should have been kept in records maintained at the school by the principal.

“But sometimes site files get discarded when principals change,” he said. “Some principals keep the file. Some principals take them with them when they leave. They shouldn’t, but some of them have done that.”

The district did not, at the time, have firm rules on how to maintain school files.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.