Saved from Dumpster: Amazing map collection makes librarians tingle

The discovery that real estate agent Matthew Greenberg made when he stepped inside a Mount Washington cottage will put the Los Angeles Public Library on the map.

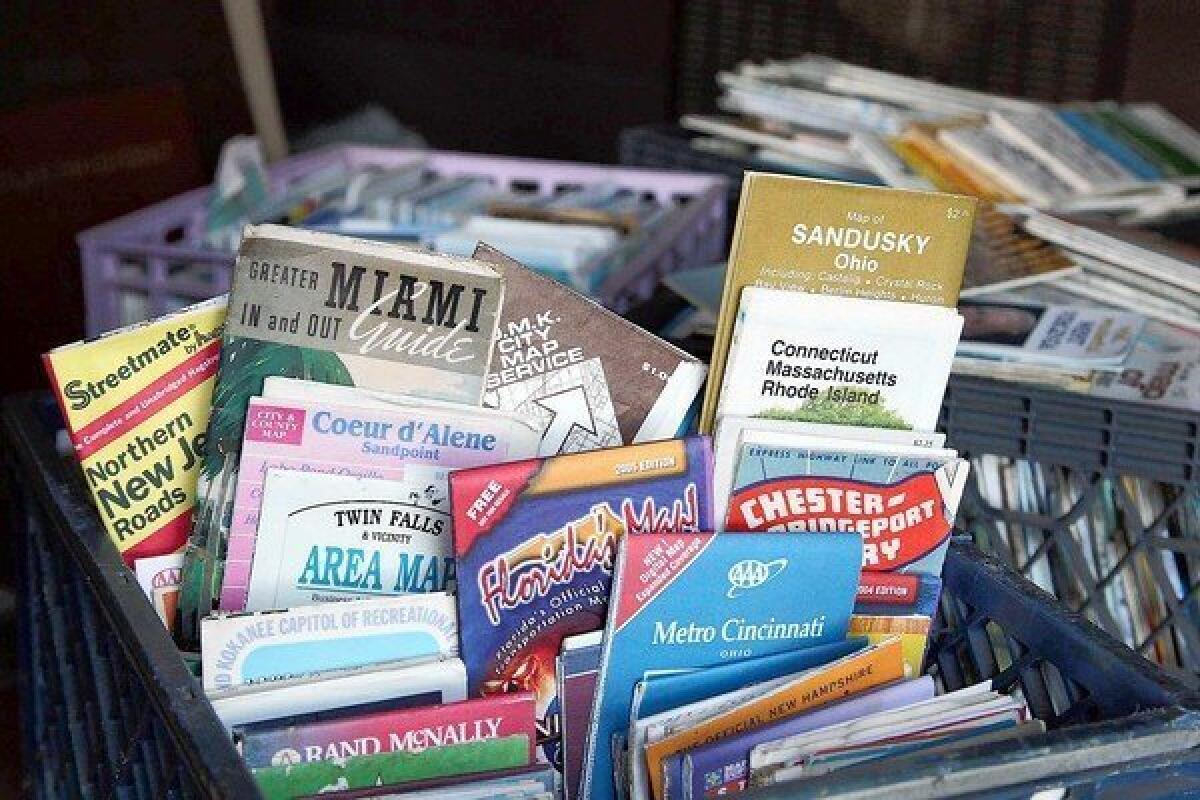

Stashed everywhere in the 948-square-foot tear-down were maps. Tens of thousands of maps. Fold-out street maps were stuffed in file cabinets, crammed into cardboard boxes, lined up on closet shelves and jammed into old dairy crates. Wall-size roll-up maps once familiar to schoolchildren were stacked in corners. Old globes were lined in rows atop bookshelves also filled with maps and atlases.

A giant plastic topographical map of the United States covered a bathroom wall and bookcases displaying Thomas Bros. map books and other street guides lined a small den.

PHOTOS: Treasure-trove of maps

The occupant of the 90-year-old cottage had died in February. Greenberg’s job was to empty the home so it could be demolished and its 18,000-square-foot lot, near the top of Canyon Vista Drive, divided into two parcels. His clients had told him to rent a Dumpster and throw away whatever he found inside.

But Greenberg couldn’t bring himself to do that, especially after he read a recent Los Angeles Times article about the Central Library’s map collection. Instead, he invited its map librarian, Glen Creason, to Mount Washington to look at the trove.

Creason called the find unbelievable. “I think there are at least a million maps here,” he said. “This dwarfs our collection — and we’ve been collecting for 100 years.”

Creason returned to the home Thursday with 10 library employees and volunteers to box up the maps. The acquisition will give the city library one of the country’s top five library map archives, behind the Library of Congress and public libraries in New York, Philadelphia and Boston, he said.

As the workers went through the tiny house, they tried to piece together the wanderlust life of John Feathers, the man who amassed the collection, apparently, beginning in childhood.

But they had little evidence to go on, and it remained a mystery exactly how and why he obtained so many maps.

Born in Massachusetts, and raised in a military family that is believed to have spent time in the Midwest, Feathers became a hospital dietitian who seems to have traveled widely. He was the companion of the home’s late owner, Walter Keller, who arranged for him to continue living there after his own death two decades ago.

Feathers died in February at age 56, leaving no known survivors. Keller’s brother and sister, Marvin Keller and Esther Baum, retained Greenberg to sell the property, which is located next to the Self-Realization Fellowship meditation center.

According to Greenberg, it was the “nagging voice of my mother in the back of my mind” that prompted him to hesitate before tossing out the maps. He has a soft spot in his heart for archives and collections; his mother, Marilyn Greenberg, is a retired university professor who specialized in library science.

It took hours for the workers to pack up the maps Thursday. Everywhere they turned, they found more. As the morning wore on, neighbors came over to watch. “John was a quiet, shy guy. But looking at all of this, I’d say the job at the hospital was clearly not his passion,” said Michelle Litchfield, who has lived two houses away for 17 years.

Volunteer Peter Hauge was startled when he moved an old stereo. “Look at this!” he shouted. “He gutted the insides of the stereo of its electronic components and used the box to store more street maps. The front of the stereo still has the knobs.”

After that, Hauge said he made a point to inspect the home’s washer and dryer and its refrigerator and oven for more stored maps, but found none.

Feathers’ trove contained both run-of-the-mill gas station and Chamber of Commerce street maps as well as historic gems, Creason said.

“He has every type of map imaginable. There’s a 1956 pictorial map of Lubbock, Texas. He’s got a 1942 Jack Renie Street Guide of Los Angeles,” Creason said. “He has four of the first Thomas Bros. guides from 1946. Those are very hard to find. The one copy we have is falling apart because it’s been so heavily used. We had to photocopy it.”

Gingerly fingering an atlas-sized 1918 map with a faded blue cover, Creason opened it up to show the National Map Co.’s “Official Paved Road” guide to the United States. The tattered pages illustrated the location of paved roads with red and blue ink.

Creason was also enthralled by the discovery of several “Mapfox” Los Angeles street guides published in 1944. Creason said in his 32-year library career he had never seen one. Also tucked into Feathers’ collection was a pocket-size “Geographia Authentic Atlas and Guide to London and Other Suburbs,” showing streets, parks, lakes and rivers that Creason dated as pre-World War I.

The house where Feathers kept his collection sits on a lot that has its own history. The site was once used by the Los Angeles and Mount Washington Railway, which was operated from 1909 to 1919 by Robert Marsh, himself a turn-of-the-century Los Angeles mapmaker and developer of the Mount Washington Hotel, now used by the Self-Realization Fellowship. A section of steel cable used to move the railway’s trolley cars up and down the steep hillside remains embedded in concrete in a corner of the lot, which is priced at $450,000.

Creason expects that cataloging and organizing the maps will take as long as a year. “We may have to apply for a grant to sort through the fold-out maps and ask for help from the Library of Congress. The collection will take up about 600 feet of shelving,” he said.

Veteran antiquarian map dealer Barry Ruderman of La Jolla would not put a price on the find. He inspected the collection Wednesday and discovered that the oldest piece was a 1592 map of Europe. Ruderman described Feathers as “more of a hoarder than a collector.” Along with his maps, Feathers also collected tiny bars of hotel soap, restaurant matchbook covers and National Geographic magazines dating from 1915 to this year.

“This person grabbed every map he could,” Ruderman said, glancing at a map of Hopkins County, Ky., in the cottage’s kitchen.

“I think he wasn’t looking so much for maps as they were finding him.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.