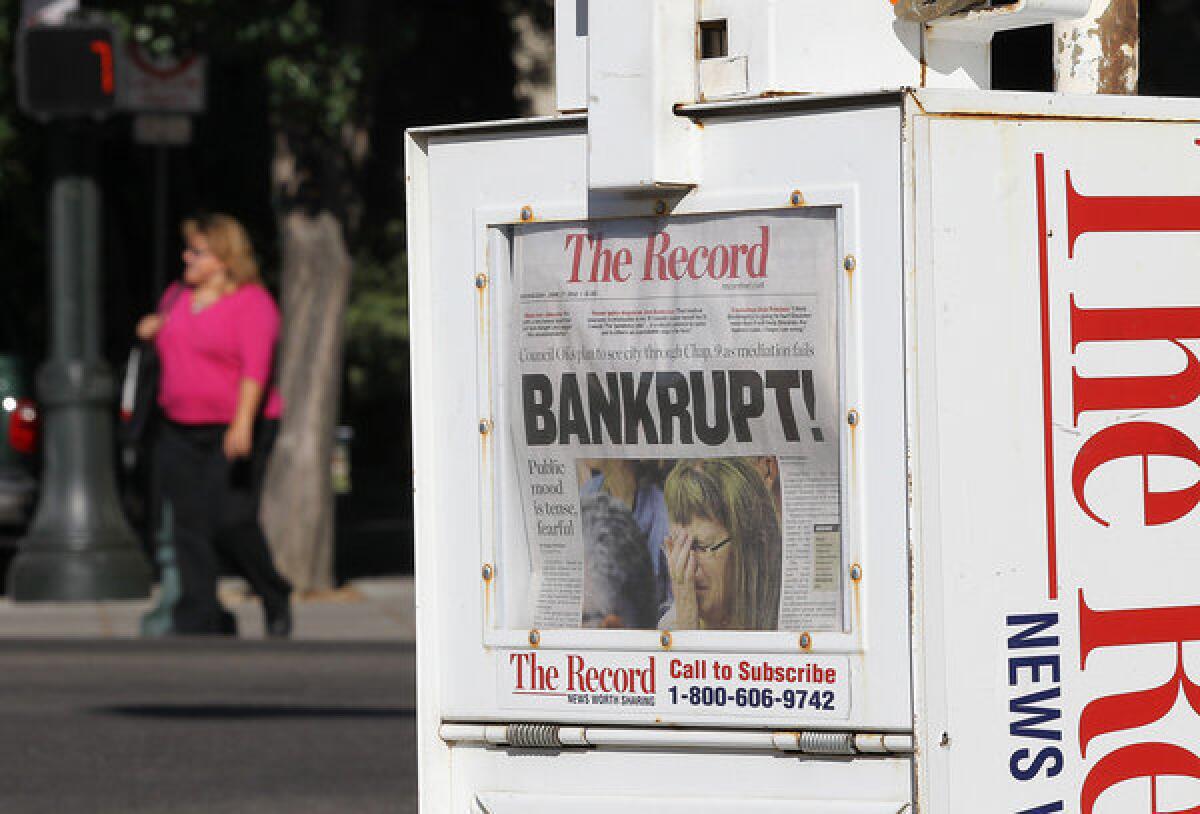

Blame all around in Stockton

After a federal judge ruled last week that the city of Stockton can reduce its debt through bankruptcy, observers began to frame the battle as one of municipal bondholders against public employees. But it’s hard to shed tears for either of them.

During the boom years, Stockton promised its future public-sector retirees free lifetime medical coverage. It also adopted rules allowing workers to spike their pensions by letting them include overtime and other payments from their final work year to calculate retirement pay.

The city also issued far too many bonds. From 2003 to 2009, on an annual budget of just $156 million, Stockton borrowed $191 million for a spending spree that included public housing, an events center and arena, parking garages and a new City Hall and police communications center.

The city also borrowed $125 million to make its required payments to the California pension fund. Yes, even during the boom years, Stockton could not afford to make its pension payments.

Since 2008, the average home price in Stockton has fallen from $407,000 to $118,500, which means that property and sales tax collections have fallen sharply too. The city has cut back severely, reducing its workforce by 25%, including deep cuts in the fire and police departments, and cutting worker pay and benefits. When it became clear that wasn’t enough to balance the budget, Stockton last year suspended $2 million of its $13 million in annual bond payments.

In its bankruptcy filing, Stockton noted that “debt taken on … in the 2000s is simply not supportable given current economic realities without devastating current city services.”

The city’s position has those who invested in the bonds crying foul. A coalition of creditors, including municipal bond funds and a company that insures government bonds against default, tried to prevent Stockton from even filing for bankruptcy. They asserted that the city wasn’t insolvent because it still had the ability to raise revenue through taxation or to cut even more deeply. They also said that Stockton hadn’t negotiated in good faith.

Last week’s ruling by U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Christopher Klein found that Stockton was indeed insolvent and that it hadn’t negotiated in bad faith. As Klein put it: “It was the choice of the … creditors to take a position as a stone wall.”

Investors are right to be nervous. The debt from which Stockton wants to free itself is not general obligation debt. That is, it doesn’t carry the full faith and credit of Stockton citizens and taxpayers.

The creditors should have understood this fact six years ago, when they freely chose to insure or purchase the bonds. The offering document warns right on its first page in big, bold, capital letters that the bonds “DO NOT CONSTITUTE AN OBLIGATION OF THE CITY FOR WHICH THE CITY IS OBLIGATED TO LEVY OR PLEDGE ANY FORM OF TAXATION.”

You couldn’t have missed it — unless you just didn’t care.

Creditors also should have known they might lose out to the state’s pension system, CalPERS, in case of a bankruptcy. California law considers its state pension fund to be a super-senior creditor, and state politicians and appointees have made it clear that they intend to keep it that way.

Investors should have contemplated the risks before lending money to Stockton on generous terms without knowing how the city planned to make good on all its promises. If investors had thought before lending, they could have turned off the money spigot then — forcing Stockton to admit, for example, that its pensions were unaffordable a good half-decade ago. Instead, bondholders prolonged the pain for taxpayers — and, now, have caused pain for themselves.

Fiscal conservatives expressed disappointment in Klein’s ruling. But if they are unhappy with public employee compensation, they should continue to persuade their fellow citizens — and elected officials — to reduce that compensation. If fiscal hawks don’t like the fact that California has anointed CalPERS as a senior creditor under state law, they should change the state law and maybe even the state Constitution, which governs that law.

And if bondholders without a full faith and credit guarantee from taxpayers don’t like the fact that the state of California considers them to rank low on the repayment scale, they shouldn’t buy the bonds.

A bankruptcy judge can’t be expected to do everybody else’s hard work for them.

Nicole Gelinas is a contributing editor to the Manhattan Institute’s City Journal. @nicolegelinas on Twitter.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.